Ecotourism of Lembung Mangrove

Entrance Gate to Lembung Mangrove Ecotourism (Photo Credit : Gafur Abdullah/Mongabay)

Overview of Lembung Village

Pamekasan Regency is the most advanced regency on Madura Island in terms of infrastructure and has the lowest poverty rate on Madura Island. Pamekasan Regency consists of 13 sub-districts, further divided into 178 villages and 11 urban villages. The regency is bordered by the Java Sea to the north, the Madura Strait to the south, Sampang Regency to the west and Sumenep Regency to the east.

Madura Island (Photo Credit : Google Maps)

The topography of Pamekasan Regency is based on elevation and slope, where the elevation ranges from 0 to 340 meters above sea level. The highest area is in Pegantenan District at 312 meters above sea level, while the lowest area is in Galis District at 6 meters above sea level.

Pamekasan Regency (Photo Credit : DKLH Kab. Pamekasan)

The location of the conserved mangrove by the community is on the eastern coast of Lembung Village with a coastline stretching 9 km. Lembung Village is one of the 10 villages in Galis Sub-district, Pamekasan Regency, Madura Island.

Lembung Village is a coastal village where the majority of the population are salt farmers and fishermen. Geographically, Lembung Village is located on the coast with an elevation from Sea Level: 500 meters. The eastern part of Lembung Village faces the Madura Strait. Lembung Village is located in Galis Sub-district, Pamekasan Regency, East Java Province, with a population of 1,273 people, consisting of 637 males and 636 females. The area covers 453,618 hectares. Lembung Village also has 4 hamlets: Lembung Utara, Lembung Tengah, Bungkaleng and Bangkal.

The people of Lembung Village are maritime agrarian communities where their main productions include rice farming, fields, livestock, ponds and sea catches. Additionally, the villagers have various occupations such as civil servants, military/police personnel, entrepreneurs, craftsmen, farm laborers, retirees, fishermen, livestock breeders, salt farmers and unemployed individuals.

Geographically, Lembung Village is located on the coast. The eastern part of Lembung Village faces the Madura Strait. Lembung Village has great potential for salt production and experiences two seasons, namely the rainy and dry seasons, like in other parts of Indonesia.

Mangroves in Indonesia

According to the SNI 7717-2020 specification, which revises SNI 2217-2011, mangrove specifications are grouped according to canopy cover area. The area of mangrove land in Indonesia according to these specifications is:

- Dense Mangrove : 70 – 90%

- Moderate Mangrove : 30-70%

- Sparse Mangrove : 0-30%

Based on the 2021 national mangrove mapping, the existing mangrove land area in Indonesia is:

- Dense Mangrove : 3,121,240 Ha (92.78%)

- Moderate Mangrove : 188,366 Ha ( 5.60%)

- Sparse Mangrove : 54,474 Ha (1.62%)

Total : 3,364,080 Ha

Mangrove Habitat Potential:

- Eroded Area : 4,129 Ha ( 0.55%)

- Open Land : 55,889 Ha (7.79%)

- Eroded Mangrove : 8,200 Ha (1.08%)

- Aquaculture Ponds : 631,802 Ha (83.55%)

- Emerging Land : 56,162 Ha (7.43%)

Total : 756,183 Ha

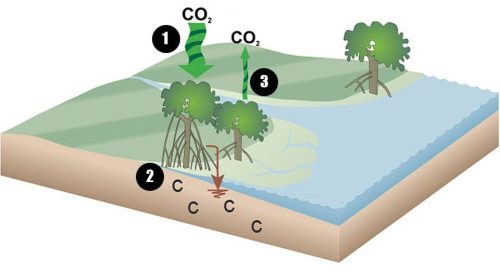

Understanding Blue Carbon

Blue Carbon is a term used for carbon emissions reserves absorbed, stored and released by coastal and marine ecosystems. The blue carbon ecosystem includes several areas such as mangrove forests, seagrass beds, saltwater marshes and coral reefs. This ecosystem, in the form of coastal vegetation, can absorb carbon much more effectively—up to 100 times faster—and more permanently than terrestrial forests. It is also said to absorb and store carbon dioxide (CO2) in their soil or sediments over long periods at rates up to five times higher per unit area than terrestrial forests.

This diagram illustrates the mechanisms by which carbon moves in and out of coastal wetlands: (1) Atmospheric carbon dioxide is taken up by trees and plants during photosynthesis. This is called sequestration. (2) Dead leaves, branches and roots containing carbon are buried in the soil, which is often, if not always, covered by tidal water. This oxygen-poor environment causes very slow breakdown of plant material, resulting in significant carbon storage. (3) A small amount of carbon is lost back to the atmosphere through respiration, while the remainder is stored in the leaves, branches and roots of plants. (Photo Credit : Sutton-Grier et al. 2014 Marine Policy)

The blue carbon potential in Indonesia is significant, reaching 3.14 million tons or about 18% of the world's blue carbon. The blue carbon ecosystem in coastal areas is crucial because long-term carbon absorption and storage help reduce the impact of climate change.

One of Indonesia's blue carbon potentials is mangrove forests. Indonesia's mangrove forests are the largest in the world, covering more than 24% of the total mangrove area globally, which is about 3.36 million hectares (Statistics_KLHK, 2023). This fact shows that Indonesia has a significant contribution to optimizing mangrove potential.

Indonesia has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 31.89% unconditionally and 43.20% conditionally by 2030. This commitment is part of Indonesia's contribution to achieving the global goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit the increase in global temperatures to below 2 degrees Celsius. To achieve this target, the utilization of potential, especially mangrove forests, has become one of Indonesia's key strategies.

To fulfill this commitment, the Indonesian government has made various efforts in rehabilitating and restoring mangrove forests. The Peat and Mangrove Restoration Agency (BRGM) and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) are responsible for rehabilitating rare mangrove areas within forest areas covering 27,160 hectares and 8,487 hectares, respectively. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (KKP) is responsible for rehabilitating rare mangrove areas outside forest areas covering 18,837 hectares, with assistance from other Ministries/Institutions along with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs).

Problems and Conflicts

Poverty along the coastlines of Indonesia is currently an unresolved national issue. Coastal communities, as the main stakeholders of the mangrove ecosystem, face various situations and challenges. On one hand, the community heavily depends on the mangrove ecosystem for livelihood and protection from natural disasters. On the other hand, economic and social pressures often push them to overexploit the mangrove ecosystems, such as converting mangrove lands into aquaculture ponds or settlements. Additionally, a lack of knowledge and awareness about the importance of mangroves in carbon absorption and climate change mitigation also poses a challenge.

Uncontrolled conversion of mangrove land into ponds is one cause of imbalance. Illegal logging of mangroves for use as building materials, firewood and clearing new land are major conflicts occurring in Lembung Village. The intrusion of water into residential areas (homes), the loss of aquaculture dykes and the loss of livelihoods due to the disappearance of farmers' ponds are consequential issues. Concerns about the continuous damage to mangroves, which could drive coastal erosion and lead to land loss and water intrusion into settlements during high tides—potentially resulting in the disappearance of Lembung Village—motivated a resident of Lembung Village to independently replant the barren mangrove land.

There is a lack of awareness and concern among the community about the long-term benefits of mangroves and their connection to the coastal ecosystem. Low levels of education correlate directly with the low economic status in fishing villages, leading to the pursuit of immediate, easily accessible benefits. Information about the benefits of mangroves is not adequately targeted and needs more substantial and attractive support and information to reach its goals.

Restoration and Conservation Efforts

In 1986, with concerns about the gradual loss of Lembung Village, mangrove restoration activities in Lembung Village were initiated by a resident of Bungkaleng Hamlet with the help of his son, Slaman. At that time, Slaman was still in junior high school, together with his father, they searched for mangrove seedlings from the remaining mangrove areas. Their activity involved collecting mangrove seedlings and planting them. Despite initial failures and the damage to planted seedlings, they persevered.

Slaman, an environmental activist who protects mangrove forests (Photo Credit : Gafur Abdullah/Mongabay)

Based on their experience, they eventually learned the right time to collect seedlings, germinate them, plant them and care for mangroves. Apart from planting, Slaman also patrolled and monitored people entering the area with logging equipment. Those caught cutting mangroves were penalized by replacing one damaged tree with 25 new trees, although not everyone followed this rule.

Over time, their restoration efforts began to show results, attracting participation from other villagers in his community. After his father's passing, Slaman found it challenging to work alone. Therefore, with the support of the community and the village authorities, the Village Forest Community Group (LKMDH) Sabuk Hijau was established in 2009. This group patrols the area in collaboration with the military and forestry department. They set up guard posts within the area to prevent tree damage, such as logging for firewood or boat anchoring. However, these guard posts were sometimes damaged or vandalized by dissenting individuals, not aligned with the vision of Sabuk Hijau.

Lembung mangrove forest (Photo Credit : Gafur Abdullah/Mongabay)

Currently, the independently managed mangrove area by LKMDH Sabuk Hijau covers 44 hectares, while the remaining 29 hectares are managed by PERHUTANI. The planted mangroves have grown well, with thick foliage making it difficult for wood thieves to enter and take wood from the area. Every Friday, LKMDH Sabuk Hijau conducts beach cleaning activities as part of their routine.

Mangrove Coffee (Photo Credit : KSDAE)

Another innovative activity by Sabuk Hijau is the production of Mangrove Coffee, Mangrove Tea and Mangrove Crackers using mangrove fruits. Mangrove Coffee is made from ripe fruits of Rhizophora stylosa species. The coffee-making activity can be carried out throughout the year, but fruit collection is done during the mangrove fruiting season. One kilogram of ripe mangrove fruit (yellow in color) is priced at Rp. 3000/kg. 35% of coffee sales are local, while 65% are sold in other regions (Jakarta, Kudus, and surrounding areas of East Java). Besides coffee, the group also makes Mangrove Tea from Jeruju leaves (Acanthus ilicifolius). Jeruju plants are known for their antimicrobial properties due to compounds like alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids and terpenoids. On average, the group earns around Rp. 400,000 per month from gathering mangrove fruits, empowering women in the coffee-making process.

Further, the Mangrove area in Lembung Village has also been developed into an Ecotourism area managed by the local community, facilitated by PERHUTANI (Indonesian state-owned forestry company) and the Department of Fisheries and Maritime Affairs (DKP). With an entrance fee of Rp. 1,000 per visitor, facilities such as bridges to enter the area, resting places and souvenir kiosks are provided.

Another positive impact is that salt farmers and fishermen no longer need to spend money on protecting their embankments from water erosion. Their embankments are now safely protected by mangroves, saving the usual cost of Rp. 3,000,000 for one reinforcement of the embankment, which can now be used for other essential needs.

From the previous discussion, we can see the socio-economic benefits of mangrove conservation directly and indirectly. Direct benefits include additional income from fruit collection, coffee and tea production and income from tourism contributions. Indirect economic value includes reduced or eliminated embankment maintenance costs.

As for indicators of economic well-being: (1) Material quality of life (2) Physical quality of life (3) Mental quality of life (4) Spiritual quality of life. According to the Central Statistics Agency, the well-being level is assessed from several aspects such as nutrition and health, education, employment, consumption patterns, housingand environment and poverty.

On the coastline of Madura Island, Instructive Co-Management is predominantly applied in mangrove management. Mangrove management has a positive and significant effect on coastal economic and health development. The economic development of the Madura Island coast is marked by increased community income, creation of new job opportunities, and improved health conditions, in line with the increased quality and quantity of mangrove conservation.

The management of mangrove forests has a significant positive impact on economic development, which includes increased income, new job opportunities, and mangrove sustainability.

Lembung mangrove ecotourism (Photo Credit : Gafur Abdullah/Mongabay)

Slaman's hard work has resulted in improved well-being for the residents of his village. His dedication to mangrove conservation earned him the Kalpataru Award in 2016. Through the development of Mangrove Ecotourism in block 61 of the Pamekasan Forest Management Unit (RPH), East Madura Forest Management Unit (BKPH), East Madura Forest Management Unit (KPH), Slaman, who is also the Chairman of the Green Belt Village Forest Community Institution (LMDH) Sabuk Hijau, won the 1st National Best Award in the 2022 Sustainable Forest Conservation Cadre (KKA) category for managing the Mangrove Ecotourism development.

Conclusion and Recommendations

- The total area of mangroves in Indonesia is 3.36 million hectares with a Mangrove Potential Area of 756,183 hectares, which includes Abraded Area, Open Land, Abraded Mangrove, Fishponds, and Emergent Land.

- Several factors contribute to the degradation of mangrove forests: uncontrolled utilization, conversion of mangrove forests for various purposes, and the lack of knowledge among communities about the functions of mangrove forests.

- The rehabilitation of mangroves in Lembung Village has ecological, economic, and social benefits that contribute to economic and social improvement.

- Support and cooperation from various parties are essential to preserve mangroves as the primary ecosystem supporting life in coastal areas.

- The success of Lembung Village can serve as an example and learning tool in saving mangroves in other nearby areas that have experienced a decline in mangrove quality, especially across the entire Madura Island region.

-YN