Reading Coastal Health Through Small Creatures: The Role of Bioindicators in Safeguarding Marine Ecosystems

Coastal areas are among the most productive yet most vulnerable ecosystems in the world. In these zones, human activities such as tourism, coastal resource use, and land-based runoff interact directly with sensitive ecological processes. Numerous studies show that coastal degradation often occurs slowly and cumulatively, making it difficult to detect through visual observation alone or through short-term water quality measurements. Therefore, approaches are needed that can capture ecosystem conditions more comprehensively and over longer time scales.

In this context, bioindicators represent one of the key approaches in coastal ecology. Bioindicators are organisms or biological communities whose biological responses reflect the surrounding environmental conditions. This approach has long been used in marine ecosystem studies because living organisms respond in an integrated way to various environmental pressures—physical, chemical, and biological. In other words, bioindicators function as “living archives” that record changes in ecosystem quality over time.

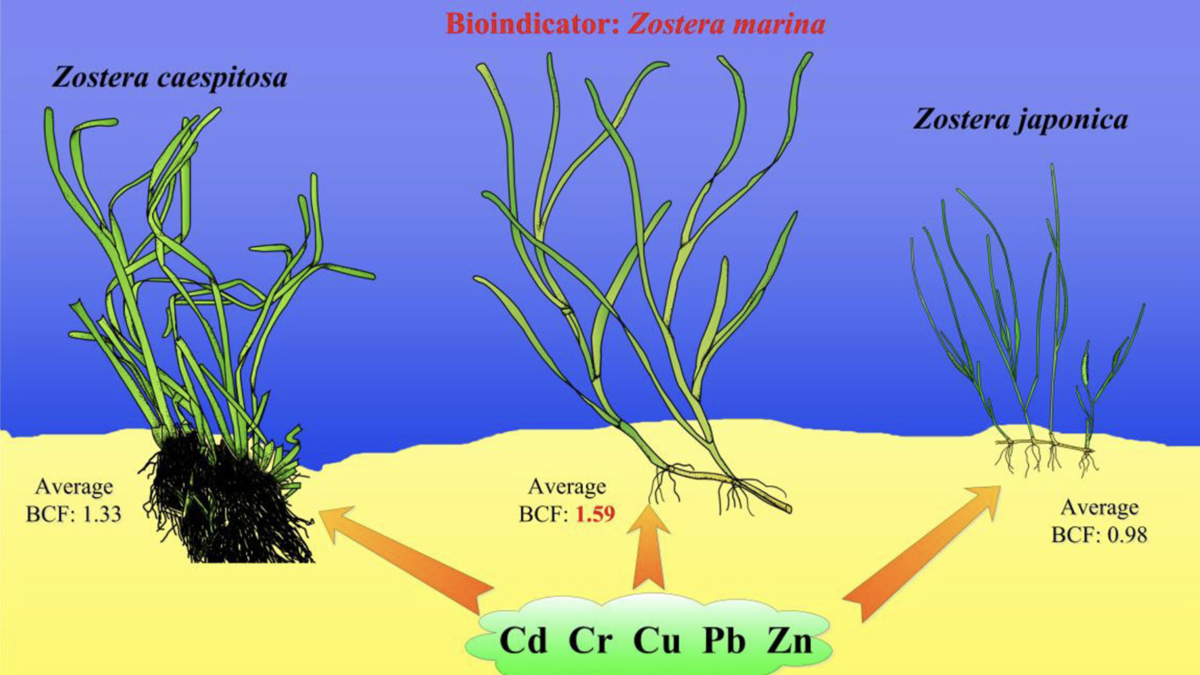

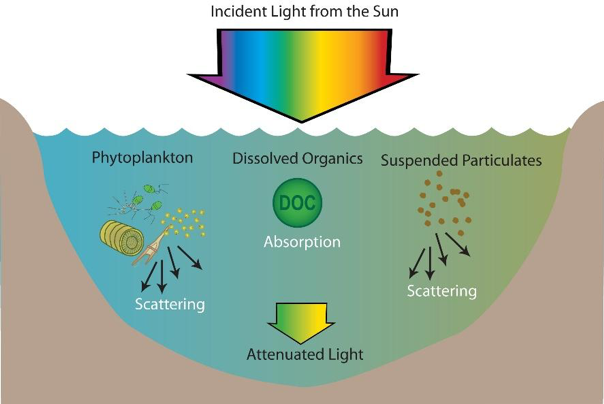

In tropical coastal regions, seagrass is one of the most frequently used bioindicators. Seagrass is highly dependent on light availability, sediment stability, and water quality, so even small changes in these parameters can directly affect its growth and coverage. Declines in seagrass cover and changes in species composition are often associated with increased turbidity, eutrophication, and human activity pressures along the coast. For this reason, the condition of seagrass meadows is often used as an early indicator of shallow-water degradation.

In addition to seagrass, macrozoobenthos—organisms that live on or within the seabed such as mollusks, crustaceans, and annelids—also play an important role as coastal bioindicators. Their relatively sedentary lifestyles make this group highly sensitive to changes in sediment and water quality. The structure of macrozoobenthic communities, reflected in species diversity, evenness, and dominance, has been widely used to assess levels of environmental disturbance and habitat stability in coastal areas. Communities with high diversity generally indicate more stable and supportive environmental conditions.

The bioindicator approach becomes increasingly relevant when linked to the concept of cumulative anthropogenic pressure. Human activities in coastal areas rarely have isolated impacts; instead, multiple pressures often interact and reinforce one another. Global research shows that these cumulative impacts are the most influential factors driving the decline of marine and coastal ecosystem conditions. Within this framework, bioindicators serve as an early warning system capable of capturing the accumulation of such impacts through measurable biological responses.

Furthermore, the use of bioindicators is not only important for academic purposes but also has direct implications for coastal management. Information derived from the condition of seagrass and macrozoobenthos can provide a scientific basis for zoning policies, coastal tourism management, and conservation efforts for key habitats. This approach aligns with the view that coastal ecosystem management must be ecologically based and involve biological indicators as a core component of environmental health assessment.

Ultimately, bioindicators teach us that coastal ecosystems have their own “language” for conveying their condition. Thinning seagrass and increasingly simplified macrozoobenthic communities are not merely ecological phenomena, but warning messages about ongoing pressures. By listening to and understanding these messages, humans have a greater opportunity to maintain coastal sustainability before the damage becomes irreversible.

“Protecting the coast is not only about building, but about listening—including listening to the messages of the small organisms that live within it.”

-Yuni Sulaiman

References

Rodil, I. F. et al. Macrofauna communities across a seascape of seagrass meadows : environmental drivers , biodiversity patterns and conservation implications. Biodivers. Conserv. 30, 3023–3043 (2021).

Halpern, B. S. et al. human impacts on the world ’ s ocean. Nat. Commun. 1–7 (2015) doi:10.1038/ncomms8615.

Bennett, N. J. et al. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 205, 93–108 (2017).