Manta Ray

Two giant oceanic manta rays feed on plankton (Photo Credit : Enric Sala/Nat Geo)

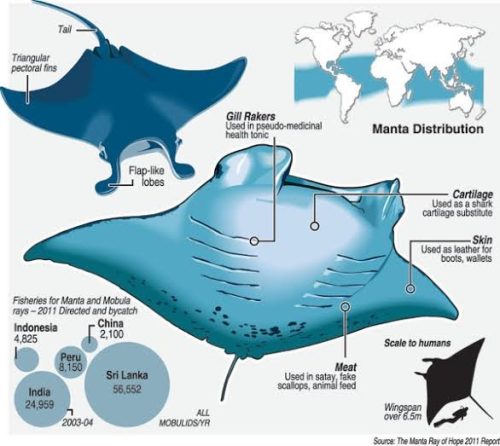

The manta ray (Manta birostris) is one of the largest species of rays in the world, with a body width ranging from 6 to 8 meters (there are reports of mantas with a body width reaching up to 9.1 meters). The heaviest weight ever recorded for a manta is around 3 tons. Its dimensions can only be rivaled by other giant fish, such as the Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus).

Manta rays are not included in the category of venomous rays commonly known, and their tails do not have stingers like most other rays. In 2022, the IUCN categorized this species as "vulnerable," meaning the species has a conservation status that is vulnerable to extinction unless effective protection and reproduction measures are taken. Threats to the manta ray population are primarily due to high fishing activity and unfavorable ocean conditions, which can lead to a decline in their population, threatening their future survival.

Manta rays are epipelagic fish commonly found at depths between 0 to 120 meters, distributed in tropical oceans worldwide, roughly between 35 degrees north latitude and 35 degrees south latitude. Their widespread presence and unique appearance have earned them various names, including "Pacific manta," "Atlantic manta," "devil fish," and "sea devil." In Indonesia, the distribution of manta rays includes tropical and temperate waters. This species can be found in waters such as Bali, West Nusa Tenggara, East Nusa Tenggara, East Kalimantan, Maluku, North Maluku, Southeast Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Papua, and West Papua. Raja Ampat Regency in West Papua Province has the largest manta ray population in Indonesia. In 2016, at least 500 individuals had been identified, consisting of 400 reef mantas and 100 oceanic mantas. Of all the mantas in Raja Ampat, almost all gather in Wayag Lagoon, which is the meeting point of the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean. Uniquely, only in Raja Ampat can both types of manta rays live together. Mantas have various local names such as cawang kalung, plampangan, and pari kerbau.

Morphology

Manta rays exhibit a variety of colors, ranging from black, blue-gray, and brown, to almost white. The color patterns on a manta’s body also vary. For instance, mantas found in the eastern Pacific have predominantly black undersides, while those in the western Pacific tend to have paler undersides. Although the exact function and cause of this color variation are not fully understood, this diversity helps scientists differentiate mantas from different regions.

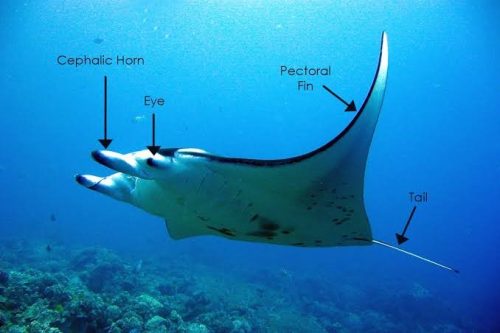

Anatomy of manta rays (Photo Credit : Manta Ray Advocates)

The skin of mantas is covered by a mucus layer that is much thicker than that of most other rays. This mucus layer is believed to protect their vulnerable skin. Additionally, mantas are considered to be more intelligent than other rays, supported by their larger brain size.

A distinctive feature of mantas is the pair of “horns” near their mouths. These “horns” are actually a pair of cephalic (head) fins that help funnel seawater containing plankton into their mouths and can be folded into their mouths. Inside their mouths, mantas have 300 small, peg-shaped teeth that are nearly hidden under the skin. These teeth are not used for feeding but are useful during mating.

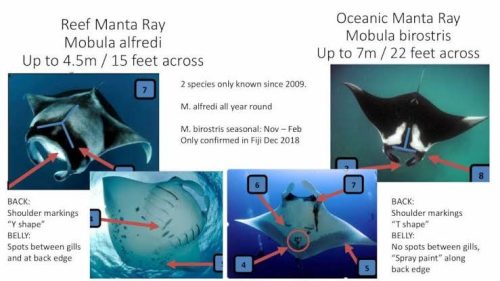

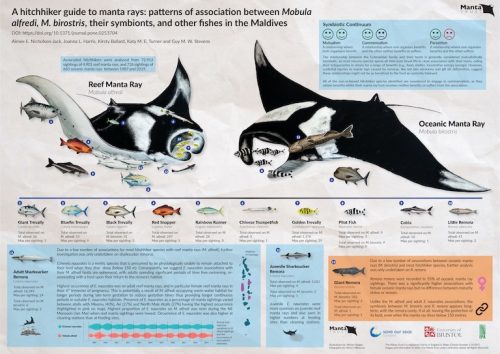

Taxonomically, manta rays belong to the family Myliobatidae, or the family of large rays. There are three species of manta rays, two of which can be found in Indonesia: the oceanic manta (Mobula birostris) and the reef manta (Mobula alfredi). The third species, Mobula hynei, is declared extinct.

Photo Credit : Marine Ecology Consulting

Reproduction

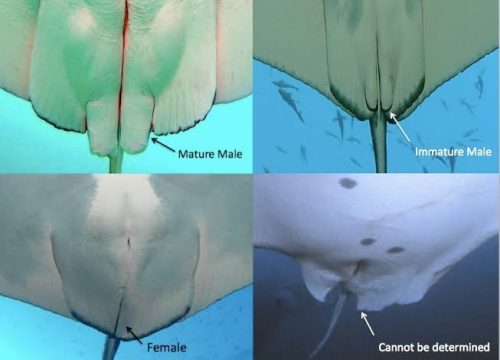

Manta rays are known to reach sexual maturity relatively late. Males are ready to mate at the age of 8 to 9 years, while females are ready at the age of 12 to 14 years. Females give birth to only one offspring every few years.

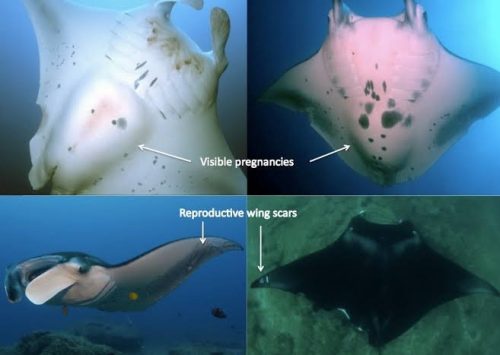

Photo Credit : MantaMatcher

According to Nesha Ichida from the Manta Project, when manta rays mate, the female manta ray can only carry one baby. This usually occurs once every 2 to 5 years.

Photo Credit : MantaMatcher

Unlike most fish, manta rays reproduce through sexual contact. Reproduction occurs through mating, unlike most fish which release sperm and eggs into the water. The male actively pursues the female for mating to occur. The female will then be pregnant for 12 to 13 months. Manta ray reproduction is ovoviviparous, where the eggs hatch inside the mother's body. A female manta can carry two baby mantas at once. The exact gestation period of mantas is not yet known, but it is estimated to last between 9-12 months. A newly hatched baby manta leaves its mother's body with its fins still folded. The baby manta becomes active immediately after it develops its fins and starts swimming. A newborn manta can have a wingspan of 1.2 meters and weigh 45 kg. Baby mantas grow very quickly; within a year, their body width can nearly double from birth. The maximum known age of manta rays is 20 years.

Edy Setyawan from Conservation International revealed that the lifespan of giant manta rays is estimated to be up to 50 years with a low natural mortality rate. Although their productive age can reach 25 years, female manta rays can only give birth to 5 to 15 offspring in their lifetime.

Role of Manta Rays in Waters

Small fish are often found near manta rays. One of the most frequently observed species near mantas is the remora fish (Echeneida sp.). This fish is commonly found attached to the underside of the manta ray using a suction-like structure on the top of its body. Remoras benefit by attaching to mantas as they are protected from predators and receive "free food" in the form of parasites on the manta's skin.

Photo Credit : Manta Trust

The Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) is known to be a primary predator of manta rays. Mantas lack defensive tools and rely solely on their swimming ability to escape from enemies, as they do not have defense mechanisms like other types of rays. Mantas are known to use their pectoral fins to strike attackers.

Indonesian waters have officially become the world's largest manta ray conservation area in an effort to protect these fish from the threat of extinction while boosting income from marine tourism. This designation, covering 5.8 million square kilometers, was made possible by a 2014 regulation by the Minister of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries that prohibits the capture and export of manta rays.

Studies by LIPI and several international organizations indicate that a living manta ray can contribute up to US$1 million in tourism revenue, while if caught, the winged fish with a maximum length of 7.5 meters is only worth between US$40 and US$500. Manta rays can generate up to $140 million, or approximately 1.33 trillion rupiah, annually in tourism revenue for 23 countries.

Threats and Conservation Efforts for Manta Rays

Photo Credit : The Manta Ray of Hope 2011 Report

The exploitation of manta rays is driven by high demand, particularly for their gills. Gills are often traded at high prices due to their believed medicinal properties. Although the demand for manta ray meat is not as strong, it is still quite popular for its soft texture and relatively high calcium and phosphorus content.

The very conservative reproductive strategy of manta rays (through mating) means that even small-scale hunting significantly affects their population levels. Maintaining or even increasing the population of manta rays, including giant species, is not an easy task.

Uncontrolled fishing practices, such as the use of large trawl nets (Pukat Harimau), also threaten the survival of manta rays.

Avoiding the consumption of traditional medicines made from manta ray body parts is one way to reduce hunting and exploitation. Additionally, conservation efforts are being carried out involving various sectors.

Intensive manta ray protection efforts in Indonesia began in 2012, especially in Raja Ampat, which is considered the second-largest aggregation site for manta rays in the world after the Maldives. In 2014, Indonesia officially designated its waters as the world's largest manta ray conservation area. Research and observations over five years, conducted in 2022, revealed that Indonesian waters are home to two of the three existing manta ray species: the Giant Manta Ray (Mobula birostris) and the Reef Manta Ray (Mobula alfredi). In Raja Ampat alone, scientists estimate there are 2,500 manta rays, with 850 being giant manta rays.

-YN