Teritip: The Hidden Potential of the Little Creature That Troubles the Shipping World

Teritip (Photo Credit : Cwmhiraeth)

Teritip is a crustacean often mistaken for a mollusk due to its hard shell. In its larval stage, teritip is free-living in marine waters, but in adulthood, it becomes a sessile organism that attaches to various hard surfaces, where it remains for the rest of its life. In shallow waters, teritip can often be found attached to submerged hard surfaces such as rocks, dock pillars, or ship hulls.

Balanus sp. can live in estuarine areas, living in a commensal symbiosis with other animals like whales, crabs, and sea snakes. Balanus sp. attaches itself alongside other marine organisms such as algae, hydrozoans, tunicates, worms, and mollusks. Balanus is widely distributed across waters due to its hard shell, which makes it resistant to significant environmental changes.

As a cosmopolitan animal, teritip can be used as an indicator of global climate change in biogeographic studies. Teritip habitats range from subtropical to tropical waters, from shallow to deep seas. If a type of teritip that typically lives in cold climates is found in warm-climate areas, it could indicate that the area is affected by global warming.

An inventory conducted since 2018 in the Maluku Islands, a global biodiversity hotspot, has found over 100 different types of teritip, such as Yamaguchiella coerulescens, Chthamalus moro, and Lepas anserifera. Among the species found, 23 were recorded for the first time in the Maluku Islands. Taxonomic research conducted by Pipit Pitriana, a researcher at BRIN Ambon, forms the foundation of biology that aims to benefit other sectors like industry, engineering, and medicine. With the potential of Maluku's marine waters, teritip has the potential to be cultivated as an exotic food product that can be exported, similar to practices in Japan and Korea.

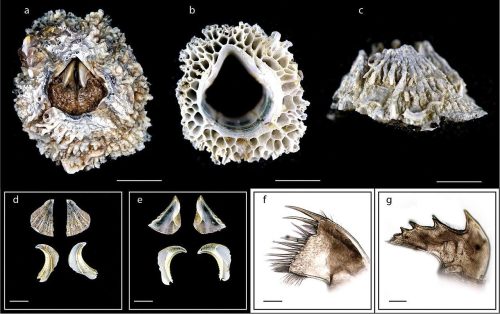

Yamaguchiella coerulescens a. upper view b. lower view c. side view d. external view of scutum and tergum e. internal view of scutum and tergum f. maxillule g. mandible (Photo Credit : Pitriana P, Valente L, von Rintelen T, Jones DS, Prabowo RE, von Rintelen K)

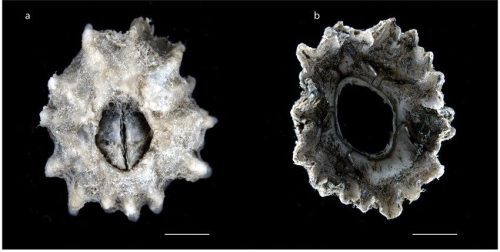

Chthamalus moro a. upper view b. lower view (Photo Credit : Pitriana P, Valente L, von Rintelen T, Jones DS, Prabowo RE, von Rintelen K)

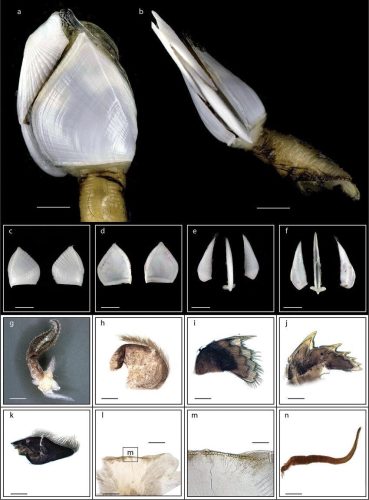

Lepas anserifera a. side view showing the capitulum and peduncle b. side view showing the carina c. external view of scutum d. internal view of scutum e. external view of tergum and carina f. internal view of tergum and carina g. cirrus I h. maxilla i. maxillule j. mandible k. mandibular palp l. labrum m. close up view on the teeth of labrum n. penis (Photo Credit : Pitriana P, Valente L, von Rintelen T, Jones DS, Prabowo RE, von Rintelen K)

Research activities in Germany and Austria on Dosima fascicularis (Floating Teritip), known for its extremely strong secretions, earning it the nickname "sea superglue." Additionally, the research aims to study its porous cell structure, which has potential applications in medicine and engineering, such as shock absorbers or cell development models.

Dosima fascicularis (Photo Credit : Notafly)

Further research on preventing teritip from attaching to various surfaces could also aid in the successful planting of mangrove trees, which have often been hindered by teritip attaching to the roots of young mangrove plants.

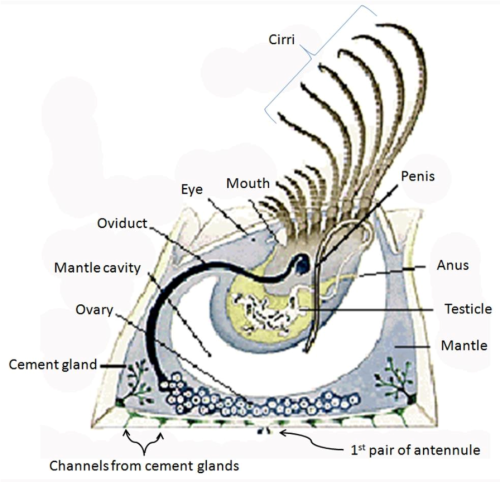

General Morphology

- Cirri : Six tentacles which are modified legs with bristles that function to capture plankton and draw food particles from the water.

- Shell : An outer hard shell made of calcium carbonate, which protects its soft body from predators and harsh environmental conditions.

- Modified Legs : The modified legs, called cirri, are used to capture plankton and food particles from the water.

Anatomy of adult teritip (Photo Credit : T.Mohamed)

Reproduction

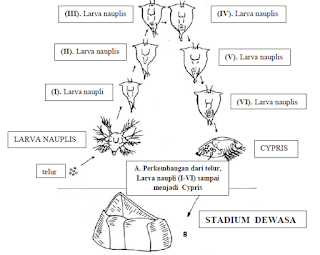

Teritip, like most other sessile animals, reproduce hermaphroditically, meaning they do not fertilize their own eggs but instead release sperm to nearby teritip. Fertilization occurs internally within the body cavity. Fertilization takes place when the sperm fertilizes the egg. The fertilized eggs are incubated in the body cavity until they become nauplius larvae. The nauplius larvae are released into the sea a month after hatching.

Nauplius Larva Stage : There are six stages, nauplius I-VI (2 to 3 weeks); cypris larvae undergo molting one to three times a week. After subsequent molting, cypris larvae form. Cypris then crawl and settle to become young teritip, eventually forming a hard shell. The attachment of teritip to ship hulls, known as fouling, can cause several significant problems.

Teritip reproduction (Photo Credit : Fusan Fuhume)

Despite their small size, teritip have a significant impact on the shipping industry. Teritip that attach to ship hulls create friction, which affects the ship's speed and fuel consumption, leading to increased maintenance costs due to the need for routine cleaning and the application of additional anti-fouling coatings to address fouling.

Though small, teritip play an important role in marine ecosystems and their impact on humans is a clear example of how small organisms can have a big influence.

-YN