Mangroves, Seagrass, and Coral Reefs as Natural Climate Buffers

Photo Credit : Issuu

Coastal areas are where climate change is felt most directly. Sea level rise, stronger waves, coastal erosion, and more frequent flooding increasingly affect settlements, infrastructure, and livelihoods along the shore. For many coastal communities, these are not distant future risks but ongoing challenges that shape daily life.

Along these coastlines, natural ecosystems play a quiet but critical role. Mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs form a connected coastal and marine system that reduces physical exposure to climate hazards. When these ecosystems are intact, they work together to weaken waves, stabilize sediments, and limit how much energy reaches the shoreline. Their contribution extends beyond ecology, directly influencing coastal safety, food security, and long term resilience.

A Connected Coastal System

These three ecosystems occupy different zones along the coast, from landward areas to offshore waters. Mangroves grow closest to land, seagrass meadows develop in shallow nearshore waters, and coral reefs form further offshore. Although separated in space, they are linked through water movement, sediment transport, and ecological processes.

Changes in one part of the system often affect the others. This connectivity means that protecting coastal communities cannot rely on a single ecosystem alone. It depends on the condition of the entire coastal system.

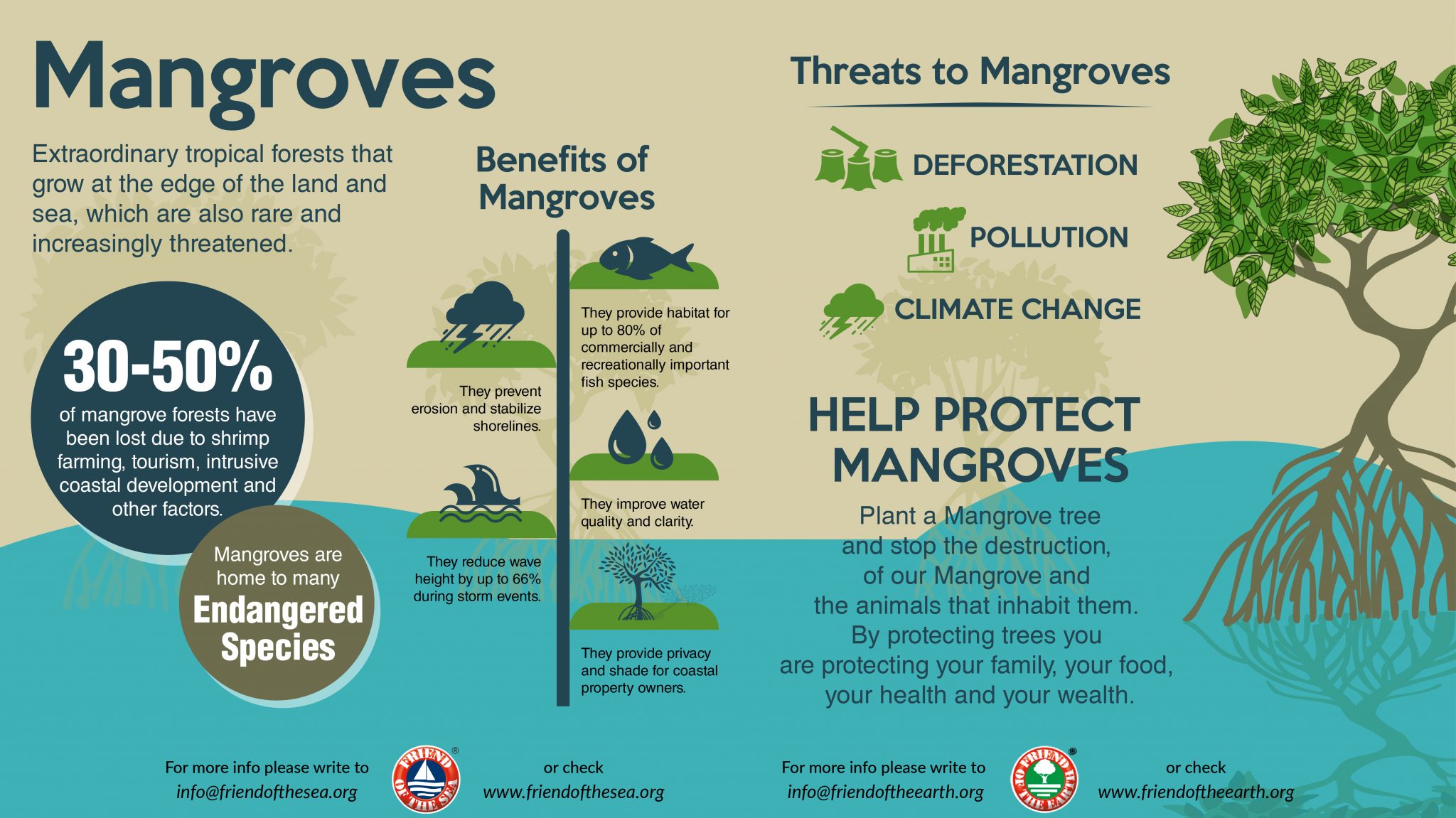

Mangroves and Shoreline Protection

Photo Credit : Rob Barnes

Mangroves form the first natural barrier along many tropical coastlines. Located at the boundary between land and sea, they are continuously exposed to tides, waves, and river discharge. Their dense and complex root systems slow water movement and capture sediments transported from both terrestrial and marine sources.

Photo Credit : FriendOftheSea

As sediments accumulate over time, shorelines become more stable and less prone to erosion. During storms or periods of high water, mangroves reduce wave energy before it reaches inland areas. This process lowers flood depth and limits damage to houses, roads, and other coastal infrastructure. For many coastal communities, the presence of mangroves directly influences whether flooding remains manageable or becomes destructive.

Mangrove ecosystems also store large quantities of organic carbon within their soils. This carbon storage contributes to climate mitigation, but it also strengthens the long term stability of mangrove systems themselves. Where sufficient space is available, this stability allows mangroves to adjust gradually to rising sea levels rather than experiencing rapid decline.

Sediments retained within mangrove forests help maintain water quality in nearby coastal waters. Where mangroves remain healthy, less fine sediment is transported offshore. Clearer and more stable water conditions then support the growth and functioning of seagrass meadows and coral reefs further along the coastal system.

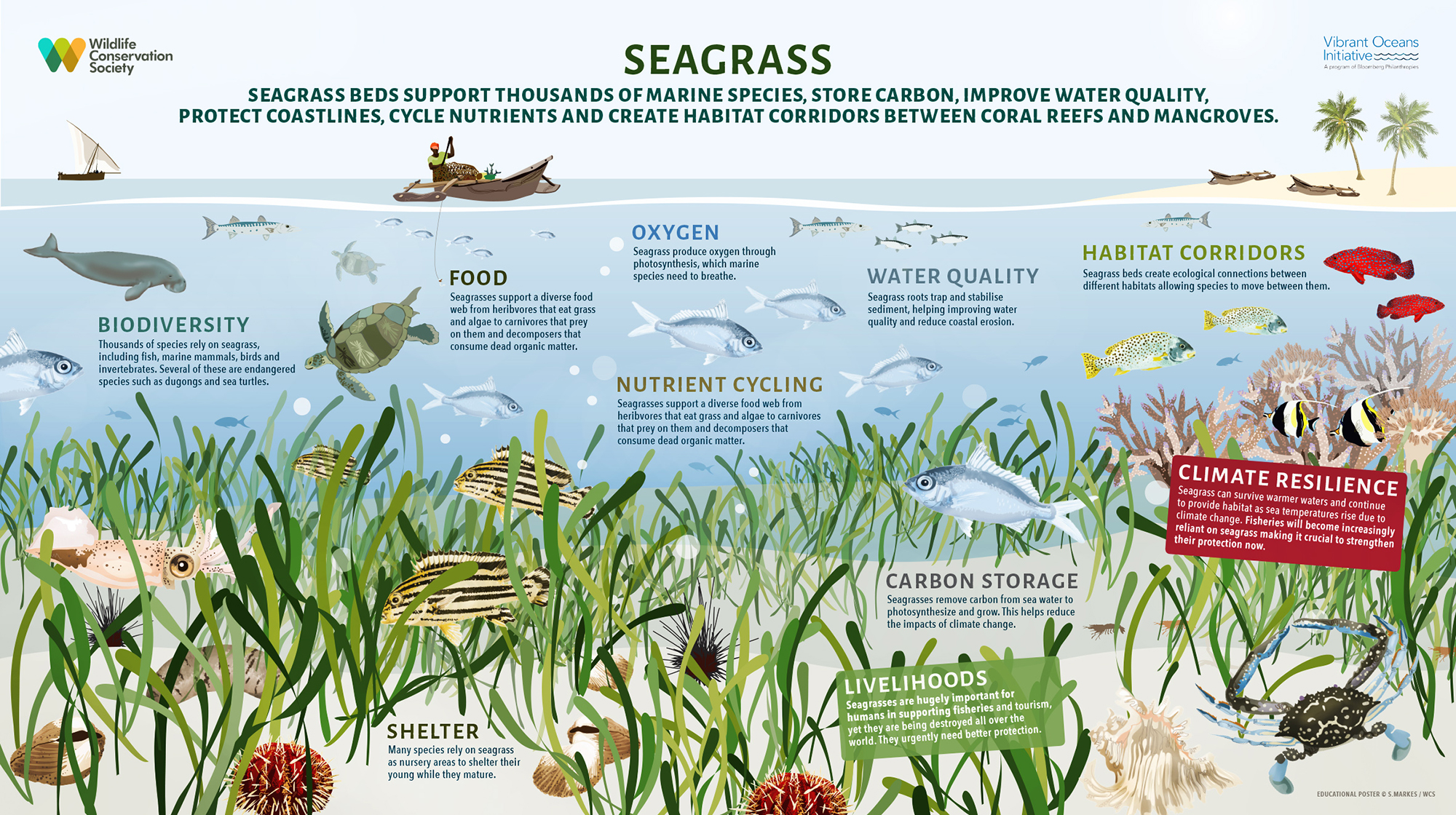

Seagrass Meadows as a Stabilizing Link

Photo Credit : people4ocean

Seagrass meadows develop in shallow coastal waters where sunlight can still reach the seabed. They are often found between mangrove forests closer to land and coral reefs further offshore, forming a transitional zone within the coastal system. Although they receive less attention than other coastal ecosystems, their role in maintaining coastal stability is substantial.

Seagrass leaves slow down near-bottom water movement, while their root and rhizome networks bind sediments together. This stabilizes the seabed and reduces the resuspension of fine particles during waves and storms. As a result, coastal waters remain clearer and less turbulent, conditions that are critical for ecosystem functioning along the coast.

Photo Credit : Wildlife Conservation Society

From a coastal protection perspective, seagrass meadows reduce erosion of the shallow seabed and dampen wave energy before it reaches the shoreline. They also support fisheries by providing nursery habitat for many fish and invertebrate species that coastal communities depend on for food and income.

Seagrass meadows are closely linked to both mangroves and coral reefs. They benefit from reduced sediment input where mangroves are intact, and in turn help maintain water clarity needed by coral reefs. When seagrass meadows decline, sediments become more mobile, water quality deteriorates, and stress increases across the entire coastal system.

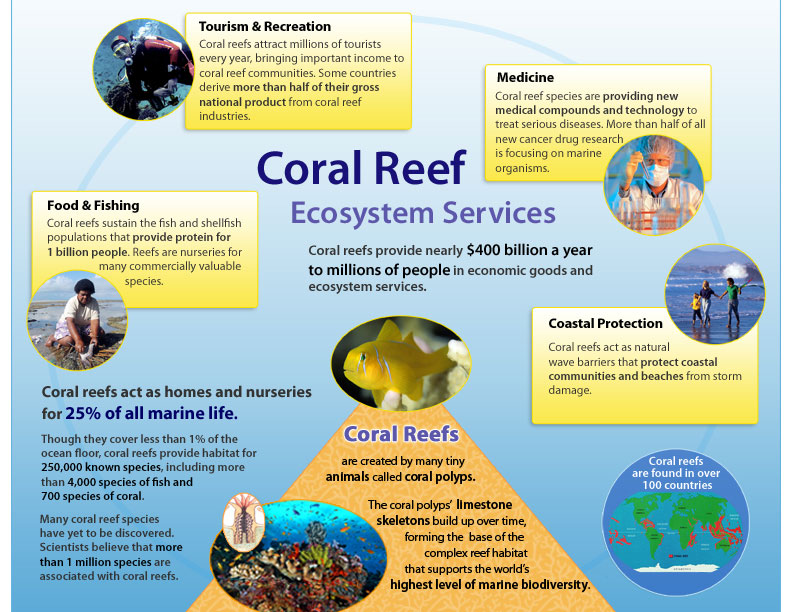

Coral Reefs as Offshore Wave Barriers

Photo Credit : Coral Reef Alliance

Coral reefs form rigid, three-dimensional structures in shallow offshore waters, where they serve as natural wave barriers. Incoming waves lose much of their energy as they break across reef crests, reducing the force that reaches nearshore waters and the coastline.

Photo Credit : Marine Science

This wave attenuation plays a major role in limiting coastal erosion and flooding, particularly during storms. For coastal communities, reefs reduce exposure to wave damage and help protect shorelines, infrastructure, and livelihoods. At the same time, coral reefs support fisheries and tourism, contributing to local economies and food security.

Coral reefs are highly sensitive to changes in ocean temperature. Prolonged heat stress can lead to coral bleaching, weakening reef structure and reducing their ability to function as effective wave barriers. When reefs degrade, more wave energy reaches shallow waters, increasing pressure on seagrass meadows and mangrove systems closer to shore.

The condition of coral reefs is strongly influenced by processes occurring nearer to land. Excessive sediment and nutrient input, often linked to mangrove loss or degraded seagrass meadows, reduces water clarity and stresses corals. Healthy reefs therefore depend on the stability of the entire coastal system, not only on conditions offshore.

Cascading Risks Under Climate Change

Photo Credit : MOHAMMED ARSYAD MD YASIN

Photo Credit : Florida International University

Photo Credit : Brett Monroe Garner / Greenpeace via Reuters file

Climate change places pressure on mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs at the same time, although each ecosystem responds differently. Sea level rise threatens mangroves in areas where landward expansion is limited, while increasing water temperatures place physiological stress on seagrass and coral reefs. These climate-driven pressures are often compounded by human activities such as coastal development, pollution, and changes in sediment supply from land.

Because these ecosystems function as a connected system, degradation in one area can quickly affect the others. The loss of mangroves increases sediment transport into coastal waters, which can smother seagrass meadows and reduce their stabilizing function. As seagrass declines, water clarity and seabed stability deteriorate, placing additional stress on coral reefs offshore. Weakened reefs then allow greater wave energy to reach the coastline, amplifying erosion and flooding risks for coastal communities.

Strengthening Coastal Protection Through Spatial Understanding

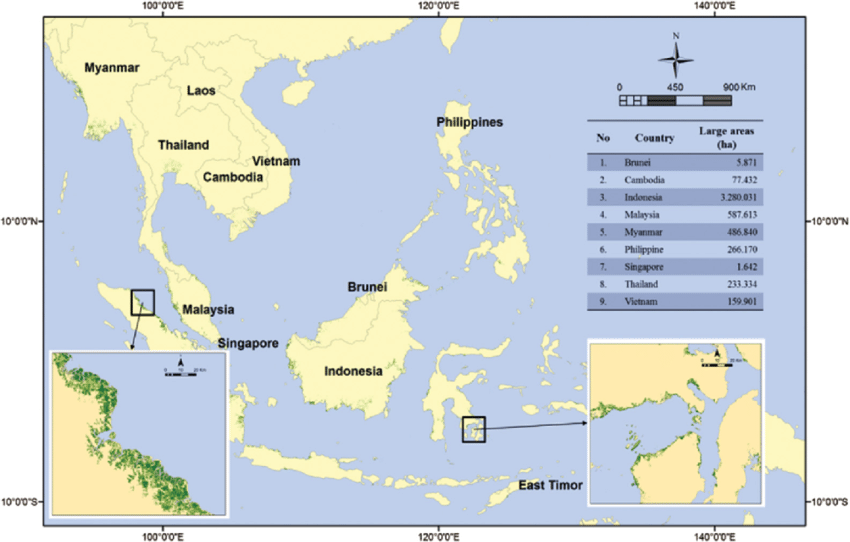

Spatial distribution of mangrove forests in Southeast Asia (Photo Credit : Wataru Takeuchi)

Spatial data makes the relationships between coastal ecosystems easier to understand. Mapping the distribution of mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs highlights where natural protection is still intact and where gaps are emerging along the coast. Changes in ecosystem extent over time reveal how these systems respond to climate stress and human pressures, while the identification of priority areas helps direct protection and restoration efforts to locations where risk reduction can be most effective.

When information from land and sea is combined, coastal planning more accurately reflects how natural systems function across the shoreline. This integrated perspective supports management approaches that recognize ecosystems not only for their ecological importance, but for their role in reducing exposure to climate hazards faced by coastal communities.

Coastal Communities at the Center

Photo Credit : AI-generated illustration

Mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs function as natural infrastructure within coastal regions. Together, they reduce wave energy, limit flooding, stabilize shorelines, and support fisheries that sustain local livelihoods. Their combined presence strengthens the capacity of coastal systems to adapt to climate change and absorb its impacts.

Protecting these ecosystems is therefore more than an environmental concern. It represents a practical investment in the safety, stability, and long term resilience of coastal communities. Understanding how these ecosystems interact, and how they change over time, is essential for shaping coastal management strategies that remain effective in a changing climate.

-Rika Novida