Silvofishery: Integrating Fishery Production with Mangrove Conservation

An aerial view of a traditional fish pond integrated with a silvofishery system using the “komplangan” planting pattern (Photo Credit : Arif Yoga Pratama)

Across Indonesia’s coasts, communities face a familiar yet difficult choice: chase short-term gains from aquaculture or protect the mangrove forests that keep their coastlines safe. Conventional shrimp and fishponds often tip the balance toward short-term benefit, clearing mangroves to expand production. The immediate harvests may be larger, but the long-term costs are high: coastal erosion worsens, fish breeding grounds disappear, and biodiversity declines.

Silvofishery, also known as Integrated Mangrove Aquaculture (IMA), offers a different path. This approach blends aquaculture with mangrove conservation, creating landscapes where seafood production and ecosystem health work hand in hand. Imagine ponds and mangrove trees sharing the same space: the mangroves filter and enrich the water, protect against storms, and store carbon, while the ponds provide fish, shrimp, or crabs for food and income.

It is a simple idea with powerful results: feeding people, protecting nature, and building resilience for coastal communities facing the twin pressures of economic need and environmental change.

What Is Silvofishery?

Silvofishery is a type of low‑input, sustainable aquaculture, in which mangroves are deliberately included within or adjacent to ponds. This method resembles organic farming, emphasizing minimal chemical use, natural habitat support, and ecosystem-based management.

Common models found in Indonesia include:

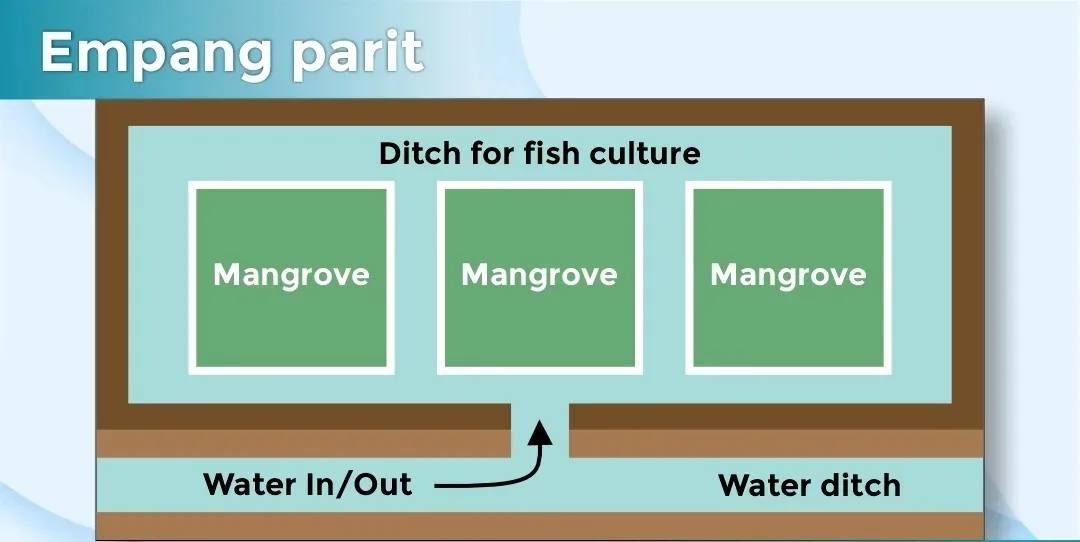

- Trench Pond (Empang Parit): Mangroves occupy much of the pond, with water-filled trenches around—typically 60–80% mangroves to 20–40% water.

Empang parit (Photo Credit : Venambak.id)

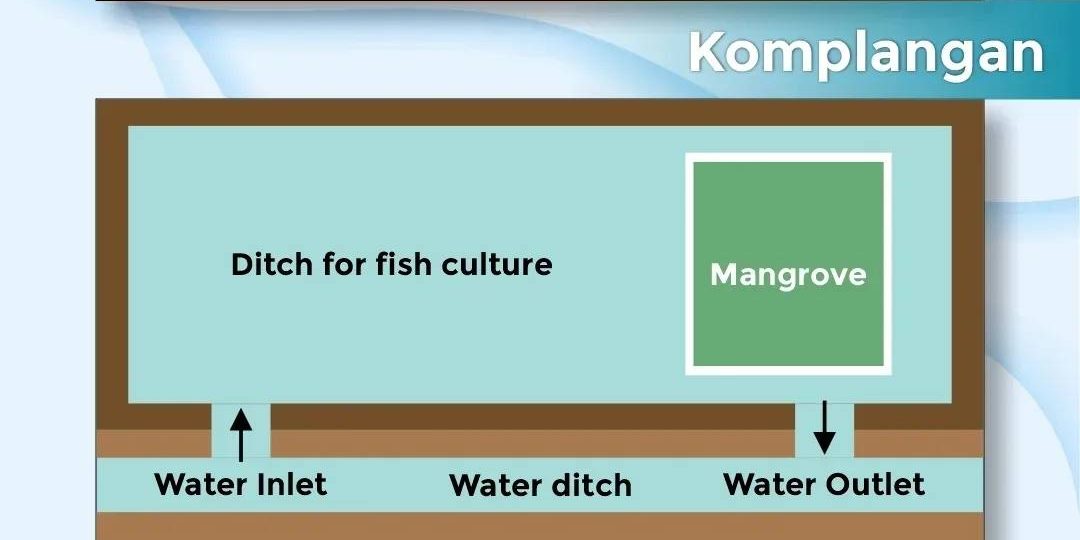

- Komplangan: This design separates mangrove conservation zones from cultivation zones using bunds; water flows through mangrove areas, acting as biofilters before entering ponds.

Komplangan (Photo Credit : Venambak.id)

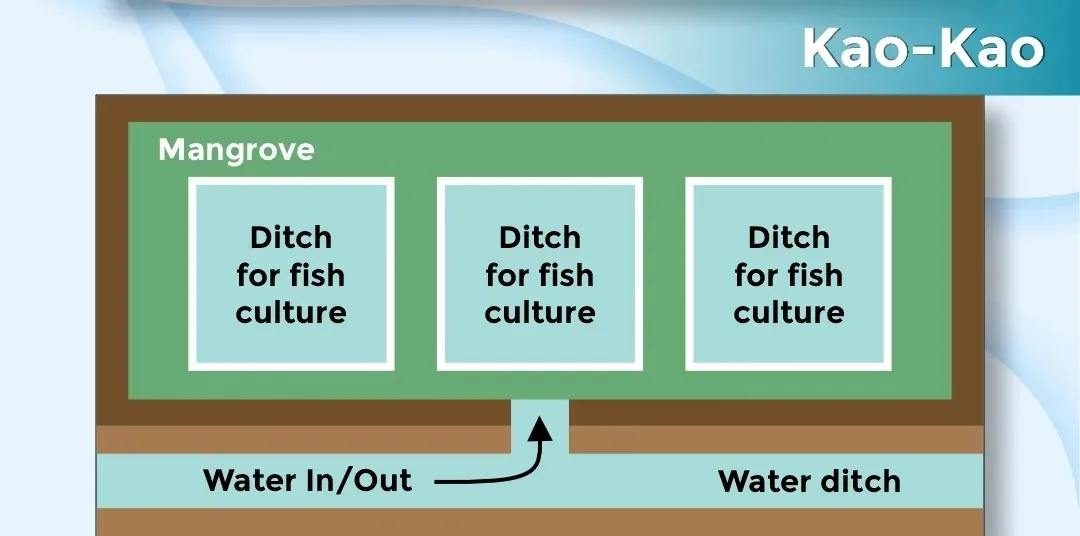

- Kao‑kao / Multivan Parit: Features multiple trenches and a single floodgate, utilizing tidal dynamics for natural water circulation.

Kao-kao (Photo Credit : Venambak.id)

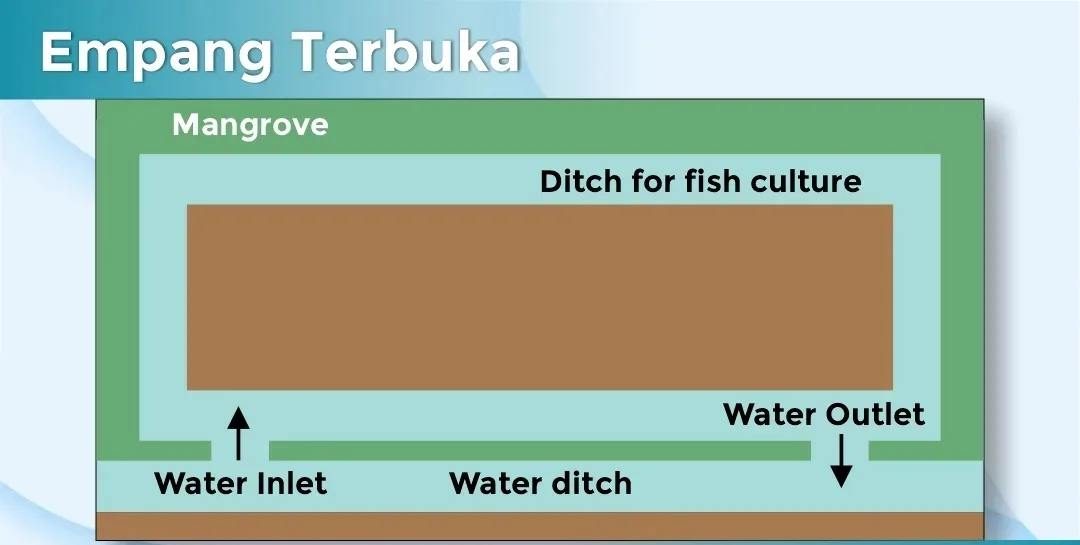

- Open Pond with Bunds: Traditional open systems with raised embankments, but with maintained mangrove corridors.

Open pond with bunds (Photo Credit : Venambak.id)

Economic Benefits

Silvofishery offers a dual-income strategy. Farmers harvest fish, shrimp, or crabs while also gaining non-timber resources from mangroves, such as honey, fruit, or craft materials.

In East Kalimantan’s Mahakam Delta, research has shown just how profitable this approach can be. Both trench-pond and komplangan systems produced over 300 kg/ha per cultivation cycle in polyculture yields—even without the use of artificial feed. In one detailed case, the komplangan design delivered net profits of about IDR 36.4 million per harvest, almost double the IDR 17.4 million from trench-ponds (Susilo, H., 2018).

A separate economic analysis using Propensity Score Matching found that farmers who adopted silvofishery earned IDR 1.04–1.10 million more per hectare each year than those with conventional ponds. Even non-adopters could expect a similar boost in earnings if they switched. Because these gains come with lower input costs—no costly feeds or heavy chemical use—silvofishery stands out as a low-input, high-return optionthat strengthens household income while restoring mangrove ecosystems (Susilo, H., 2018).

Ecological Advantages

Mangroves in silvofishery systems are far more than “background trees.” They play active, vital roles in keeping the coastal environment healthy and productive.

- Blue Carbon Storage

Mangrove ecosystems are among the most effective natural carbon sinks on the planet. Their dense root systems and waterlogged soils trap large amounts of organic carbon—often storing up to 3–5 times more carbon per hectare than tropical rainforests. In a silvofishery, this means every harvest is accompanied by long-term climate benefits. By locking carbon in their biomass and soils, mangroves help slow the pace of global warming while protecting local communities from climate-related threats.

- Biodiversity and Nursery Habitat

Mangroves create a safe, sheltered environment for juvenile fish, shrimp, crabs, and other marine life. Their tangled roots serve as a protective maze, reducing predation and increasing survival rates for young aquatic species. This not only supports the productivity of silvofishery ponds but also replenishes surrounding wild fisheries—helping maintain biodiversity in the broader coastal ecosystem.

- Water Filtration and Quality Control

In designs like the Komplangan model, pond water flows through mangrove stands before entering cultivation areas. As the water passes through, the mangroves act as a natural filter: trapping sediments, absorbing excess nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus), and breaking down organic waste. This process improves water clarity and quality, which can lead to healthier stock, reduced disease risk, and less need for chemical treatments.

Silvofishery and Food Security

Silvofishery strengthens food security by producing high-quality, locally sourced protein in a way that protects the environment. Unlike conventional aquaculture that often damages ecosystems, silvofishery maintains the natural services provided by mangroves, meaning seafood production can continue year after year without degrading the resource base.

By integrating mangroves into pond systems, farmers can cultivate multiple species at once: shrimp, milkfish, crabs, and even seaweed, reducing the risk of crop failure and ensuring a more reliable food supply. This approach also reduces pressure on wild fisheries, giving overfished coastal waters time to recover and helping maintain marine biodiversity.

Real-world results from Sidoarjo District, East Java, show the system’s potential:

- Shrimp yields ranged from 17.9 to 363.8 kg/ha/year, depending on pond design, management practices, and mangrove cover.

- Seaweed production reached between 1,920 and 14,120 kg/ha/year, providing an additional, nutrient-rich food source and a valuable cash crop.

These figures highlight that silvofishery is more than a conservation measure, it’s a practical farming system that supports diverse and nutritious diets while providing steady income for coastal families. In times of climate uncertainty and global seafood supply fluctuations, such locally managed systems can act as a safety net for food availability and community resilience.

Case Studies at a Glance

- Brebes, Central Java

In Sawojajar Village, Brebes, farmers have adopted the Komplangan silvofishery model, integrating milkfish (Chanos chanos) and whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) in mangrove-based ponds. The design channels tidal water through mangrove buffers before entering the ponds, naturally filtering out excess nutrients and improving water quality.

On average, each hectare produces 1–1.4 metric tons of milkfish per year (from two harvests) and 500–600 kilograms of shrimp annually. These yields are achieved without relying heavily on artificial feeds, reducing both costs and environmental impact. Farmers note that the mangrove buffer not only stabilizes pond conditions but also reduces sediment buildup, making maintenance easier.

- Sidoarjo, East Java

In Sidoarjo, Integrated Mangrove–Aquaculture (IMA) or silvofishery has found real-world application—not as a niche model, but as a practical path toward sustainable aquaculture. The findings from a 2024 study offer a clear snapshot of how this system works there:

- Shrimp yields (combining tiger shrimp and vannamei): between 17.9 and 363.8 kg per hectare per year.

- Seaweed production: ranges from 1,920 to 14,120 kg per hectare per year.

- Mangrove placement: Mostly along pond embankments, covering about 5% of pond area, with minimal coverage on the pond bottom (8–10%).

These figures reflect a diverse, multi-product system—shrimp and seaweed grown side by side, supported by mangrove buffers. The mangroves serve as both a physical barrier and a natural regulator, helping maintain water quality, reduce erosion, and support ecological balance. Smaller pond sizes and better-managed plots were generally more productive, suggesting that farmer capacity and careful design play big roles in success.

This model in Sidoarjo shows that silvofishery isn’t just a theory—it’s a practical, on-the-ground system that delivers real yields and real benefits, all while keeping mangroves standing.

Conclusion

While silvofishery has proven its value in boosting incomes, protecting coastlines, and securing local food supplies, its long-term success depends on a few key factors. Well-designed pond layouts, regular mangrove maintenance, and active participation from the farming community are essential to keep both productivity and environmental benefits strong.

With these elements in place, silvofishery can continue delivering positive results for people and nature alike. It stands as proof that we don’t have to choose between food production and environmental protection; both can flourish together. For Indonesia’s coastal communities, this means not just surviving in the face of climate change, but thriving with healthier ecosystems.

-Rika Novida